M O E I N N E D A E I

Ten Years of Sensemaking :)

ABOUT ME

I am a design researcher and systems thinking practitioner working at the intersection of design, complexity sciences, and politics. Born in 1991 (Iran), I bring a cross-cultural lens to challenges such as energy poverty, public health, and pandemics. My work blends storytelling, speculative design, and dialogic methods to navigate complexity and connect diverse voices for democratic decision making.

This photo was taken around 1994 at my grandmother’s house in Torbat-e Jam, Iran, where I spent much of my childhood. The environment—rich with local artistry and folklore—left a lasting impression on me and continues to shape my creative practice.

In the image, I’m sitting with my older cousin on a handmade carpet, likely woven by one of my aunts in the late 1980s. The carpet features traditional patterns, possibly inspired by local animals, and was originally made for praying during summer time. Behind us, there’s a large clay pot that was once essential for making homemade tomato paste, and a bigger container used to ferment pickles—both prepared especially for large family gatherings and traditional rituals.

The tree in the background is a barberry bush, native to the region. Its berries, along with saffron, are key ingredients in Tahchin—a classic Persian dish often called 'chicken cake'—a beautifully layered and richly flavored centerpiece of Iranian cuisine.

MY CV

MY JOURNEY

My earliest memory of being drawn to design goes back to when I was ten, during weekend visits to Kānoon-e Parvaresh-e Fekri-e Koodakān (Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults) in my hometown in Iran. While my family browsed or attended workshops, I immersed myself in books on geography, art, and astronomy. Encouraged by my parents—both teachers, my mother a geography teacher—I spent hours tracing maps, sketching imagined landscapes, and creating personal worlds.

One day, I came across Design: A Concise History by Thomas Hauffe. The text was far beyond my reading level, but the images of furniture, tools, and architectural layouts revealed design as a fusion of art, geography, and science. That discovery became my first true connection to design literature and ignited a curiosity that has guided me ever since.

That spark led me to pursue industrial design, completing both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree, with a Master of Design Sciences from Amirkabir University of Technology in 2017. After a brief role at Nipler, one of Iran’s leading furniture firms, I returned to academia as a junior lecturer at the University of Tehran.

In 2018, I moved to Canada to work as a research assistant at the University of Windsor. Collaborations with colleagues at Windsor and Waterloo expanded my focus toward service design, systems thinking, and social innovation. This shift—from product design to systemic design—eventually took me to Belgium, where I completed a PhD at the University of Antwerp, exploring the dialogic role of design in social innovation.

Research

My research focuses on community engagement and citizen empowerment through interdisciplinary approaches, with emphasis on challenges such as pandemic preparedness, energy poverty, and technological destabilization. I am particularly interested in democratizing design practice and developing participatory methods that support more equitable and just social transitions.

By integrating design with systems thinking, I explore how design can foster holistic, action-oriented responses to complex issues. Grounded in creativity, form-giving, and the progressive dimensions of design science, my work positions design as a medium for systemic change. A central strand is the co-design and facilitation of dialogic processes, including the Design-Driven Conflicts (DDC) framework. DDC draws on methods from adjacent fields to critically examine antagonistic actors and create new associations essential for addressing real-world challenges.

Some are thoughtful on their way,

Some are doubtful, so they pray.

قومی متفکرند در مذهب و دین

قومی به گمان فتاده در راه یقین

Methodology

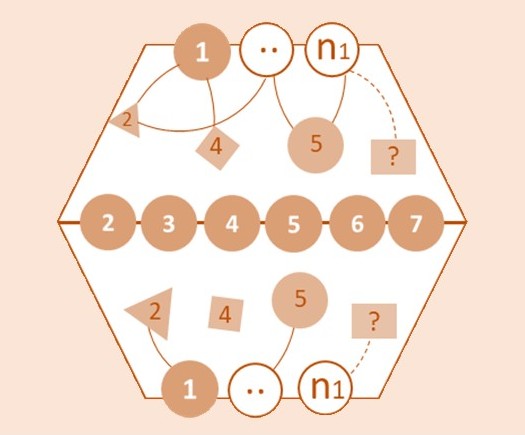

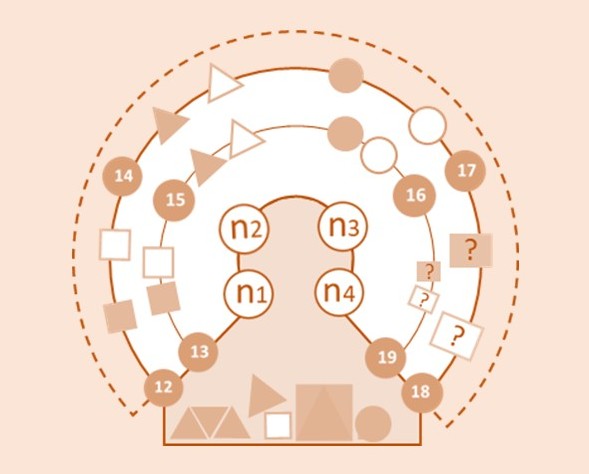

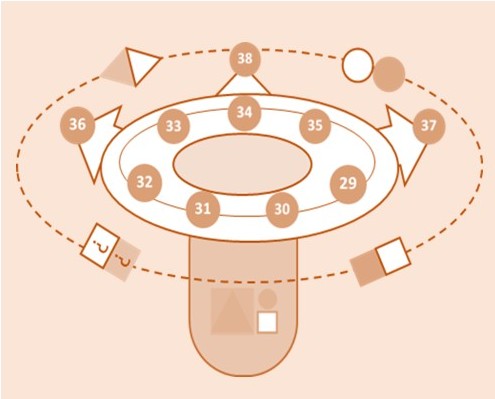

During my PhD research, I developed the Design-Driven Conflicts (DDC) Approach—a systemic design method that connects designerly ways of knowing with insights and practices from other disciplines. The DDC is an interactive, process-oriented framework designed to facilitate constructive dialogue at the process level and network-building at the outcome level, ultimately accelerating mindset and systemic transformation. The method has undergone three cycles of refinement. In its latest iteration, the DDC focuses on fostering meaningful deliberation, enabling higher-order learning, and supporting both structural and cognitive transformation across multiple levels of a system or organization. The DDC Approach is structured around five sequential and cumulative phases, each with distinct objectives and tools:

1. Mapping the Context

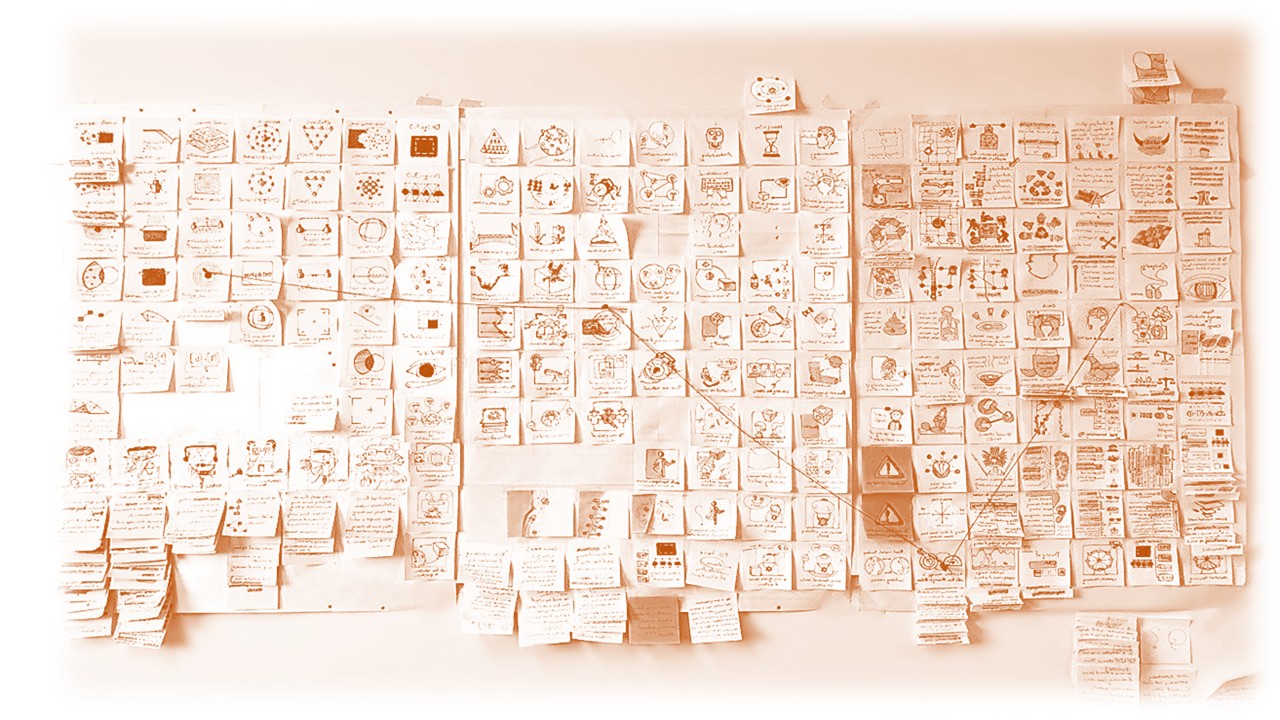

This phase begins by mapping the situation of rivalry—analyzing the broader context, identifying key actors, and understanding their relationships through the lens of shared and individual resources. The DDC offers a unique typology of resources and tools to connect archetypes based on these assets, enabling a nuanced view of the ecosystem.

2. Exploring Power, Rivalry, and Imbalance

Next, the focus shifts to unpacking power dynamics and rivalries among stakeholders. This phase uncovers tensions, injustices, and root causes of conflict. The insight here is that rivalry often stems from perceived imbalances or denied access to power. The DDC provides a distinctive framework for categorizing different forms of power and offers tools to visualize the complexity of power relations.

3. Actors’ Journey

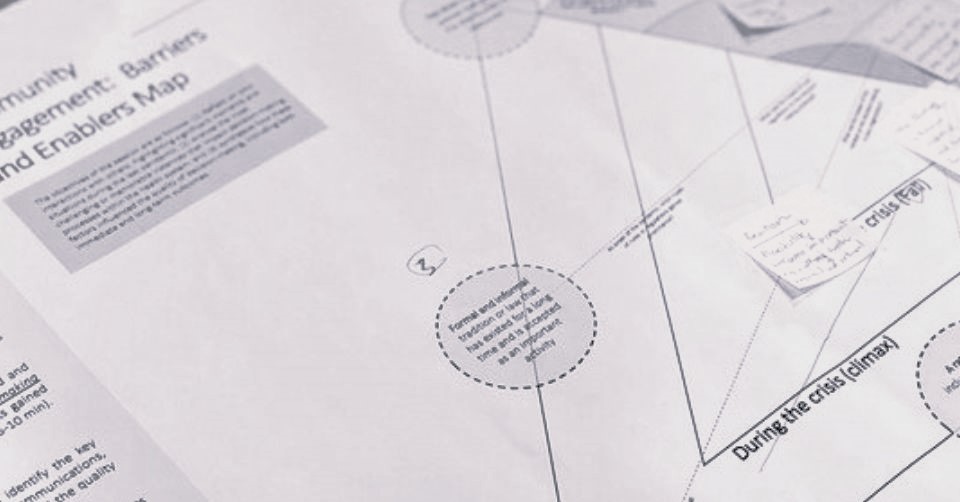

Once rivalry sources are revealed, participants embark on the Actor’s Journey—a creative and reflective process that explores the roots of conflict across past, present, and potential futures. This phase encourages participants to map their experiences visually and narratively, ultimately identifying underlying motivations, barriers, and enablers. The DDC provides a context-sensitive framework, along with tools to illuminate and zoom out from individual and collective perspectives on conflict.

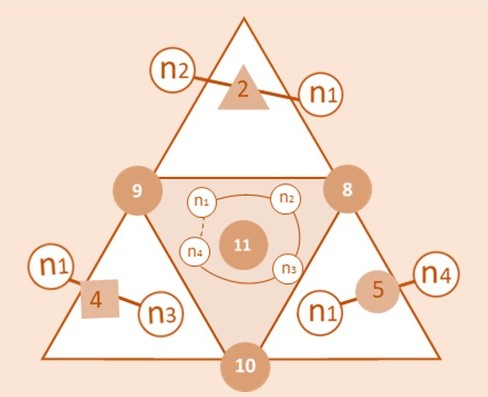

4. Problematization and Frame Innovation

Building on previous phases, this step transitions from framing conflict to reframing the problem. Participants shift perspectives, build new connections, and identify common ground. The DDC introduces a novel framework for designing new boundary objects, reordering stakeholder positions, and envisioning shared “passage points”—emergent equilibria from which collaborative futures can take shape.

5. Narrative Structuring

In the final phase, participants co-create a shared narrative structure to scale insights, solutions, and strategic interventions. These narratives are designed to strengthen connectivity and alliances, while avoiding undesired futures. The DDC provides a set of narrative design tools and prompts that help translate systemic insights into inclusive, actionable messages that can guide future decision-making.

The DDC Approach has proven particularly effective in complex, multi-stakeholder environments, where deep dialogue and systemic insight are critical to enabling transformation. It is especially suited for contexts marked by entrenched conflict, uncertainty, and power imbalance—offering a creative yet rigorous pathway toward collective sensemaking and structural change.

Mapping the Context

Mapping the Context

Power and Rivalry Exploration

Power and Rivalry Exploration

Actors’ Journey

Actors’ Journey

Frame Innovation

Frame Innovation

Narrative Structuring

Narrative Structuring

Portfolio

My design portfolio spans a broad spectrum—from physical product design to services and complex systems. Over time, this journey underwent significant transformation. I no longer approach product design solely as a response to user-centered needs. Instead, I now understand products as components of larger systems: social materials, relational tools, and boundary objects whose meaning and functionality emerge through dialogue and interaction among diverse actors. In this sense, my designs are inherently political, social, and cultural. Between 2011 and 2015, my work focused primarily on product design. From 2015 to 2018, my attention shifted toward service and systems innovation. Since 2018, I have concentrated on designing methods, practices, and frameworks for addressing complex, systemic societal challenges. This includes planning tools for community engagement, blueprints for participatory processes, and the design of rituals and practices intended to leverage the collective power of publics in transforming rigid or entrenched systems. Many of my earlier works were recognized or shortlisted in design competitions, and one project—Katour—was awarded a national patent.